|

APA to NIMH: We’re Here, You’re Nowhere Near, Deal With It

May 6th, 2013

David Kupfer, chair of the DSM-5 task force, shot back at Tom Insel, head of NIMH today with a statement that even by the standards Kupfer has set over the last five years is immensely obfuscating.

The promise of the science of mental disorders is great. In the future, we hope to be able to identify disorders using biological and genetic markers that provide precise diagnoses that can be delivered with complete reliability and validity. Yet this promise, which we have anticipated since the 1970s, remains disappointingly distant. We’ve been telling patients for several decades that we are waiting for biomarkers. We’re still waiting. In the absence of such major discoveries, it is clinical experience and evidence, as well as growing empirical research, that have advanced our understanding of disorders such as autism spectrum disorder, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia.

Where to start? How about with that “we’re still waiting”? You’re still waiting? How about all the people whom you have diagnosed with what you insist are real illneesses (even if you acknowledge that they aren’t) caused by biochemical imblances (which you know don’t exist) and treated by drugs (whose mechanisms you don’t understand). They’re still waiting for your knowledge to catch up with your claims, and the idea that your clinical experience and empirical research somehow add up to more than a stopgap measure that is increasingly problematic, that has spawned a drugging of the population that is going to look to future historians like the lead contamination of the Roman water supply does to us–this idea is really beginning to wear thin.

But that;’s not the best part. The best part comes here–after the obligatory defense of DSM-5 as “the strongest system available,” leaving out the part about how it’s pretty much the only system available.

RDoC is a complementary endeavor to move us forward, and its results may someday culminate in the genetic and neuroscience breakthroughs that will revolutionize our field. In the meantime, should we merely hand patients another promissory note that something may happen sometime? Every day, we are dealing with impairment or tangible suffering, and we must respond. Our patients deserve no less.

RDoC is the NIMH initiative, harebrained in its own way, to find the neurocircuitry of psychopathology and develop a diagnostic system based on it. NIMH has a long time frame for RDoC, ten yeaqrs or so. But they’re not issuing any promissory notes, except maybe to congress to whom they are promising research results in return for appropriations. The people being asked to take psychiatry on faith are the patients, and the people soliciting the credit are psychiatrists, especially the psychiatrists of the APA. We still,they are saying, after 150 years, don’t know what a mental illness is, we gave up a long time ago on trying to figure it out, we can’t agree on how to identify the mental illnesses that we think might exist, we just spent $25 million to make a diagnostic manual that, by our own measure, is worse than the last one, and we can’t even articulate a decent defense of it that doesn’t sound like saying we know it’s a mutt but it’s our mutt and it protects our house and if it Biedermans on the floor or Nemeroffs on the carpet or once in a while Abilifies the neighbor’s cats, well, that’s just the cost of having us around, and so you should just trust us, and by the way if you don’t, then you either don’t care about the mentally ill or you are just an antipsychiatrist following Tom Cruise because he’s so cute.

I mean, if the DSM-5 ain’t a promissory note, then I don’t know what is. and like many promises issued by confidence men, it’s not worth the paper it’s printed on.

No Comments »

NIMH to APA: Drop Dead

May 3rd, 2013

A truly remarkable event today. Tom Insel, director of the National Institutes of Mental Health, decided to say out loud what he’s been saying quietly for a few years now: that the US Government has lost faith in the DSM. And the problem, he says, is not really the DSM-5, which he says will be little different from DSM-IV, and that this is the problem. Here’s his analysis

The strength of each of the editions of DSM has been “reliability” – each edition has ensured that clinicians use the same terms in the same ways. The weakness is its lack of validity. Unlike our definitions of ischemic heart disease, lymphoma, or AIDS, the DSM diagnoses are based on a consensus about clusters of clinical symptoms, not any objective laboratory measure. In the rest of medicine, this would be equivalent to creating diagnostic systems based on the nature of chest pain or the quality of fever. Indeed, symptom-based diagnosis, once common in other areas of medicine, has been largely replaced in the past half century as we have understood that symptoms alone rarely indicate the best choice of treatment.

So the problem is the DSM itself, the way its descriptive approach can’t be anchored in something beyond itself, which is why none of the mental disorders it lists are valid. And, Insel concludes “people with mental disorders deserve better.”

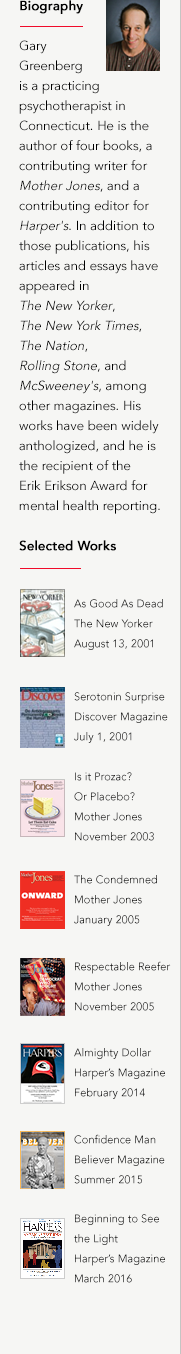

This isn’t the first time Insel has gone public with his contention (which is virtually unassailable) that the DSM does not offer validity. He talked to me about this for The Book of Woe. “There’s no reality to depression or schizophrenia,.” he said. Indeed, the idea that there is a reality to them has dominated–and in Insel’s view hamstrung–research for more than three decades. “We might have to stop using terms like depression and schizophrenia because they are getting in our way.” And he didn’t stop there. “Whatever we’ve been doing for five decades,” he told me, “it ain’t working. And when I look at the numbers–the number of suicides, the number of disabilities, mortality data–it’s abysmal, and it’s not getting any better.. All the ways in which we’ve approached these illnesses, and with a lot of people working very hard, the outcomes we’ve got to point to are pretty bleak…Maybe we just need to rethink this whole approach.”

It’s a stinging rebuke, and the timing of his blog post makes it even more so. Two weeks before the DSM-5 comes out, Insel indicts the manual. It’s as pointed as it gets at his level: he’s taking the APA to task for not having found a way out of its “epistemic prison”– a term coined by Insel’s predecessr at NIMH, Steve Hyman, who first expressed these concerns in 1999. Hyman likened the job ahead to repairing an airplane while it is flying. Now Insel has suggested that we all might be better off if they just landed the thing and let the passengers look for another flight.

3 Comments »

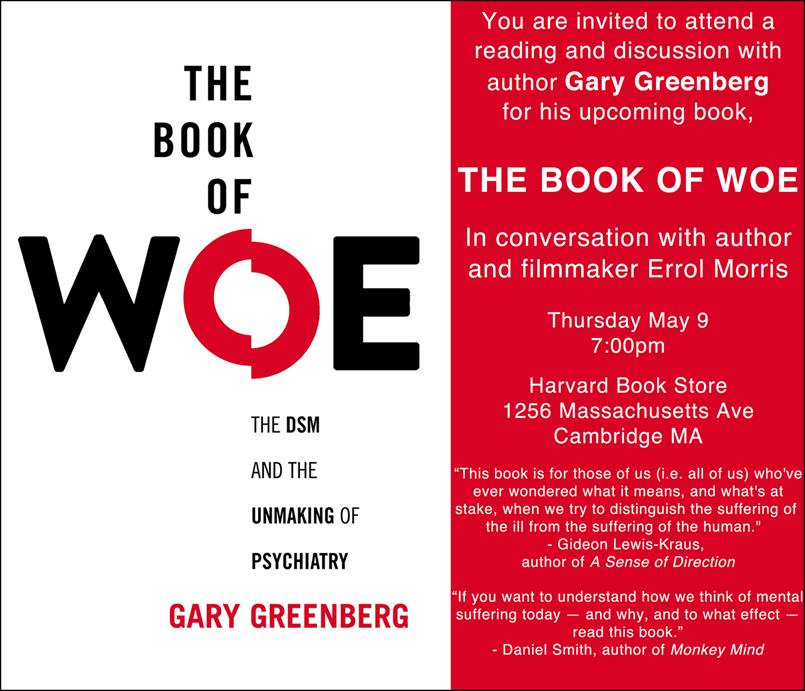

Invite to my Cambridge event, May 9

May 2nd, 2013

With a special guest

No Comments »

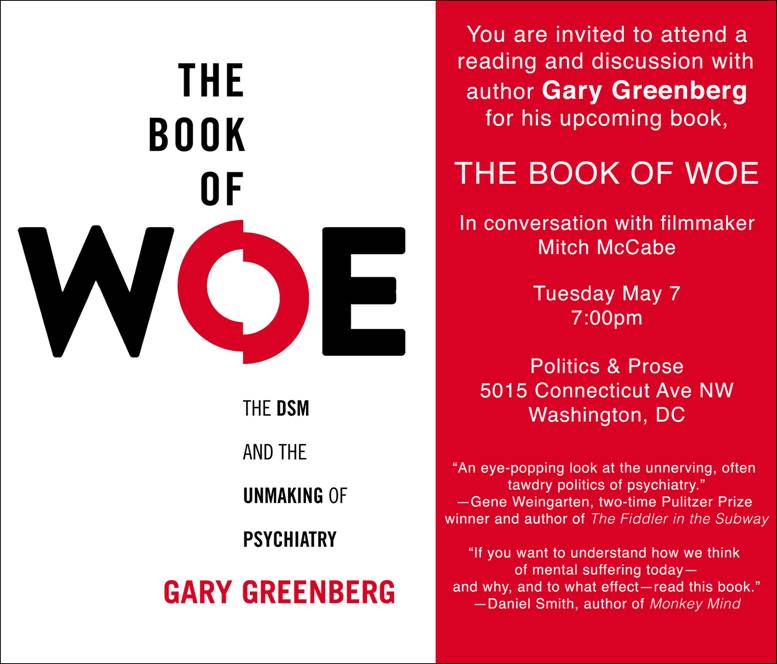

Invitation to my DC reading

May 2nd, 2013

Actually, not a reading at all, but a conversation with Mitch McCabe, who is making a film about the DSM.

Come one and all!

No Comments »

Hellzapoppin

May 2nd, 2013

A busy 24 hrs.

A NY Times review, in which Dwight Garner says I pace the psychiatric stage like a cross between George Carlin and Gregory House. I have to share space with Allen Frances’s Saving Normal but on the other hand the review ran on the front arts page, so I’ll settle.

A Nature review (probably need a subscription, but I’ll post in the reviews page soon. By David Dobbs, who calls BOW a “splendid and horrifying read.” It’s a nice, chunky review.

A Q&A at atlantic.com. Which is really funny, or something like funny, because I had no idea it was a Q&A. I kept wondering why the writer, Hope Reese, was asking me questions that seemed intended to get me to recite my book, when she could get all that by reading the book (which she clearly had done) and spare herself the transcribing. Answer: she wasn’t writing an article. She was going to write what I said, verbatim. Whoops. I am definitely more House than Carlin, that is, more growly than funny, and I say some pretty intemperate things, like “They should just take the damn thing [the DSM) away from them [the APA]. But only a couple are embarrassing.

A blog post at newyorker.com that I thought would convince people that I really don’t think disease is a biochemical category, but I was wrong.

A nice interview on CBC, public radio in Canada, to be broadcast later in the month.

And best of all, lots of happy-for-me emails from friends and family. My self-loathing is at an all-time low today.

1 Comment »

|

|

|