|

More on Grief

March 3rd, 2013

When it comes to criticism of the DSM-5, the loudest and most trenchant voices belong to those who think it’s going to extend the reach of psychiatry further into everyday life. Allen Frances is leading this charge, but he’s joined by Christopher Lane, Paula Caplan, and just about every other sentient being who’s not on the DSM-5 committees. (That would include me; I’m sure if I searched the phrase “extend the reach” in the searchable pdf file of my book that my publisher made the mistake of providing me with, I would find it often enough to make me cringe. But I won’t.) And when they lodge this charge, the case in point is often the soon to be defunct bereavement exclusion, that little diagnostic codicil that currently prohibits doctors from diagnosing people in mourning from being diagnosed with depression for the first two months after their loss. Bereft of the bereavement exclusion, the criticism goes, the DSM-5 will result in more people diagnosed with depression, more antidepressant prescriptions, and more diseasing of America.

The wisdom of crowds is a beautiful thing, unless you’ve ever actually been in one. Having spent way too much of my pre-1995 life at Grateful Dead shows, I have had the opportunity to do just that. Even when it’s pretty, it’s scary, and if you don’t believe me, just watch Triumph of the Will.

Anyway, I digress. (I can’t help it. I haven’t been in a synagogue more than five times in thirty years, but still the Jew lies deep in me.) Point is, when so many people are saying the same thing, even when that thing is quite plausible, even (or especially) when you agree with it, it’s time to wonder about it, or maybe about yourself. So to the question: Will removing the bereavement exclusion really lead to more psychiatric diagnosis?

In a way, it’s hard to imagine psychiatry extending its reach any further. I mean, it’s already reaching so far you can feel it palpating your prostate (or, I suppose, your ovaries, if you are lucky enough not to be of the gender that possesses those walnut-sized cancer factories embedded deep in its collective groin). The DSM-IV, like the DSM-III, has a psychiatric diagnosis to suit just about any complaint you might have about the life of your psyche. That’s not an accident. Diagnostic expansion was part of the mission of the DSM-III, the one that has been the template for diagnosis since 1980: not only to provide the criteria for discerning a particular psychiatric disorder, but to provide psychiatric disorders for everything that ailed us. Bob Spitzer, the Khalid Sheik-Mohammed of the DSM-III, was a nosological diplomat, and he recognized that if he stuck with only the 21 criterion-based diagnoses (of really severe mental illnesses like schizophrenia and manic depression) that had been developed when he started the revision, he’d lose the support of the rank and file, who needed their depressive neuroses and their anxiety reactions if they were to stay in business.

Now that’s not to say that psychiatrists weren’t already reaching deep into our psyches. Of course they were, but they weren’t doing it by declaring us mentally ill. They were doing it by providing psychoanalysis to the walking wounded, transforming the language of the self in the process, but without diagnosing any of that population with what could plausibly be thought of as a medical illness. That’s what changed with the DSM-III. Psychiatrists, for mostly parochial reasons (like saving their profession from charges of pseudoscience), started to give quasi-medical names to our pain. When the drug companies got interested in psychiatric drugs, those names became extremely useful. And the two industries have been doing the tango ever since.

But none of this would have worked without a market. There is a demand side to the economy of mental disorder. In the three decades since the DSM-III was introduced, the impetus to declare ourselves sick gathered the force of a constant windstorm. So long as you’re willing to join the ranks of the diseased, it blows at your back. To say, “I am clinically depressed” is to stake a claim to many goods: sympathy, tolerance, time off from work, the right to take mind-altering drugs on the insurance companies’ tab every day without being accused of being a stoner. To say, “I have Asperger’s” opens other doors (which the APA is going to shut; that one worked too well). And so on. There’s a premium on illness; it’s increasingly how we define ourselves, how we demand resources from society, how we understand our lives. And not just mental illness. There’s a reason health care is gobbling up more and more dollars every year, and it ain’t all the fault of greedy doctors and drug companies. It’s also because, as Peter Sedgwick said in 1972, and as i never get tired of quoting, “The future belongs to illness.” Forty years later, the future is here.

Or, to put it another way, the market may have reached saturation. I mean, how much more saturated can it get? Already, bereavement exclusion or not, the DSM provides criteria and labels by which half of us will suffer a mental illness in our lifetimes. That may be because the DSM is an evil disease-generating book. But it may also be because consumers know what they want and psychiatrists know how to give it to them. Removing the bereavement exclusion may not increase the market but only reapportion the share from other diagnoses, in the same way that opening a Lowe’s next to a Home Depot does not necessarily create more DIY home improvers, but only gives them a better choice of where to go to buy faucets.

So here’s my prediction: the removal of the bereavement exclusion (and the DSM-5 in general) won’t put the fingers of psychiatry further up our collective rectum. (or is it recta?) It will only give it a new orifice to probe.

1 Comment »

Paging Dr. Bronson

February 28th, 2013

Speaking of death wishes, the APA may be considering taking out a contract on Joel Dimsdale. He was the head of the Somatic Symptoms Disorders work group, the DSM-5 committee in charge of revising criteria for, you guessed it, psychosomatic disorders. That category is a quagmire, largely because of the confusions we’ve inherited from four hundred years of mind/body dualism, but that’s a story for a different day. The story for today is what Dimsdale said to ABC News.

Background: The DSM-5 is introducing Somatic Symptoms Disorder a diagnosis for which patients will qualify if they have “one or more somatic symptoms that are distressing and/or result in significant disruption in daily life,”‘ and if they have “persistent thoughts about the seriousness” of the symptoms, “persistent anxiety” about them, or devote “excessive time and energy” to them. Up late at night googling that pain in your gut? Be careful, you might be mentally ill.

I’d fully deconstruct this, but I’m supposed to be proofreading my book, and besides I trust you can see just how stupid this diagnosis is. In case you can’t then check out Allen Frances’s blog about it. The point here is what happened when ABC asked Dimsdale to comment on the objections being raised by people whose “somatic symptoms” are severe or complex enough to make persistent thoughts and anxiety inescapable and who must devote lots of time and energy (sat in a waiting room lately?) to them. Adding psychiatric diagnosis is just insult to injury, they said, and will only help doctors–who famously can’t stand patients who refuse to have something they can cure–dismiss them as nutcases.

“Some people feel like a diagnosis is a Scarlet Letter, but actually those in the DSM-4 were quite stigmatizing and pejorative,” Dimsdale said, by way of justifying the change. You would think that a guy smart enough to be a doctor would not invoke a novel whose villain has the same last name as he does, who is in fact one of the most notorious bad guys (and hypocrites) in American literature, but that is not the dumbest thing he said. The dumbest thing he said was, “If it doesn’t work, we’ll fix it in the DSM-5.1 or DSM-6.”

Not that this is not exactly the way that the DSM-5 leaders think. Indeed, it’s a version of something they’ve said repeatedly: that the DSM is a living document, not a Bible. (Forgetting, of course, that many religious people, although perhaps not Hawthorne’s Dimmesdale, think the Bible is a living document.) But to say this in the context of explaining a diagnosis that could be applied to just about anyone with a serious or debilitating disease, to acknowledge that they (and the rest of us) will be the involuntary subjects of a massive public health experiment, to bring attention to the APA’s apparent obliviousness to the real world effects of the DSM, to what happens to people when they are diagnosed and undiagnosed–really, I’ve been around this story for two years now, and even I find this shocking.

I’d say the APA would have to clean up this mess. But they’ve gone into hiding. Or more accurately, they’re just running out the clock, which they can do because they own the ball. But I wonder if behind the scenes they’re taking Dr Dimsdale out to the woodshed. Or the stocks.

Update: A reliable source assures me that Dimsdale knows full well who his namesake is and was just making an inside joke. Which is pretty funny, I’ll admit, although I doubt he intended all the layers of irony. But (and this is admittedly the pot calling the kettle black) it’s sort of cavalier, given the stakes. You gotta know your audience.

No Comments »

Does the American Psychiatric Association Have a Death Wish?

February 26th, 2013

The American Psychiatric Association has placed an advertorial in JAMA touting the virtues of the DSM-5. It’s a classic of the form–as they say in Texas, all hat and no cattle, or, as I say in my forthcoming Book of Woe, all clothes and no emperor.

“Many of the revisions in DSM-5 will help psychiatry better resemble the rest of medicine,” they write. This has been the dream of psychiatry since about 1847, when the APA was first founded (although then it was known as the Association of Superintendents of American Institutions for the Insane): to be taken seriously by the rest of medicine. And at least since 1917, when the APA (by then known as the American Medico-Psychological Association) heard from the head of its committee on nomenclature that diagnostic chaos was undermining the specialty’s credibility, it has seen the diagnostic manual as crucial to its standing in the medical profession, and in the world at large.

So have they succeeded? Is the title of the JAMA piece–“DSM-5: The Future Arrived”–accurate? For that matter, does it even make sense? Is arrived a past tense verb, meaning that the DSM-5 is some kind of visitation, as if the future showed up one day on the APA’s doorstep and left behind this message? Or is it a gerundive, a verb form used as an adjective? In which case, you have to wonder exactly what an arrived future looks like, and how it differs from one that is still traveling.

Anyway, I digress. Plus which I am sick of helping the APA explain itself. So I’ll let their words do the talking.

Many of the revisions in DSM-5 will help psychiatry better resemble the rest of medicine, including the use of dimensional (eg, quantitative) approaches. Disorder boundaries are often unclear to even the most seasoned clinicians and underscore the proliferation of residual diagnoses (ie, “not otherwise specified” disorders) from DSM-IV. But a large proportion of DSM-5 users will not be psychiatrists; most patients, for instance, will first present to their primary care physician—not to a psychiatrist—when experiencing psychiatric symptoms. The use of definable thresholds that exist on a continuum of normality is already present throughout much of general medicine, such as in blood pressure and cholesterol measurement, and these thresholds aid physicians in more accurately detecting pathology and determining appropriate intervention. Thus DSM-5 provides a model that should be recognizable to nonpsychiatrists and should facilitate better diagnosis and follow-up care by such clinicians.

I dare you to parse this passage without exploding your own head. No, here, let me do it for you. I’ve been taking Vaccutrix, the new drug that keeps your head from exploding when parsing nonsense, and which I would recommend for anyone unfortunate enough to have to follow the logic of psychiatric diagnosis. The first sentence promises that the DSM-5 will make psychiatry fit into modern medicine by providing dimensional measures, i.e., ways to measure disorders that resemble the methods doctors use to diagnosing other conditions. The second sentence reminds readers that diagnostic boundaries are porous and poorly defined, which means that accurate diagnosis is hard–so hard that even the specialists can’t do it, let alone the primary care docs whom most people see first. The third sentence suggests that the best way to make this whole thing easier is to have measures like blood pressure and cholesterol that help set the diagnostic thresholds and that bring psychiatry in line with common sense, which tells us that most people’s psychological problems are extreme versions of normal behaviors or experiences.

Now here is where you would expect the APA to tell you what they have done to make diagnosing mental disorders more like measuring blood pressure and less like throwing darts, and thus to bring about the Arrived Future. But that part seems to be missing. This doesn’t stop them from leading their last sentence with “thus,” as if they had actually proved something in the paragraph. Which they did not. They merely reasserted what they wrote at the outset: that the DSM-5 is going to bring psychiatry in line with medicine. They have restated their premise as their conclusion, using the old schoolboy trick of inserting a “thus” in front of the topic sentence and declaring QED. It’s the equivalent of the army declaring victory in Vietnam as they beat a retreat, only in this case there aren’t videos of people clinging to the runners of helicopters taking off from the embassy roof. (At least not yet. Wait until the DSM comes out. And my book.)

I said I was tired of explaining the APA, but I can’t resist. They made this fundamental logical error for a reason–indeed for the same one that the schoolboy makes it. Which is that they don’t have any evidence, and it’s not because the dog ate their homework. It’s because there are no dimensional measures in the DSM-5. They tried to develop and implement them, but the effort was hurried and chaotic and poorly planned and ultimately soundly rejected by the membership of the APA. The dimensional approach was going to be the signal achievement of the DSM-5 (that is, after the first signal achievement, the tying of neuroscientific findings to DSM disorders, had to be abandoned for lack of evidence); it didn’t pan out. The APA leadership is understandably reluctant to own up to this fact. What is astonishing, and nearly inexplicable, unless you’ve been watching this whole train wreck unfold, is that it would insist–in JAMA, no less, the flagship product of teh AMerican Medical Association–that they had succeeded where they had failed, and to think that that little magic word–thus–would somehow win the day for them.

Does the APA have some kind of death wish?

PS=–Lest you think this is my antipsychiatrist animus speaking, this is from a source inside the DSM-5 revision effort:

This statement has no relationship to the actual DSM-5. There are dimensional measures in the non-official Section III, however. But that still has nothing to do with “definable thresholds that exist on a continuum.” I would have hoped that had the reviewers of this editorial actually known anything about what DSM-5 was going to look like they would have prevented such statements from being included.

No relationship to the DSM. In other words, no relationship to reality. In other words psychotic.

7 Comments »

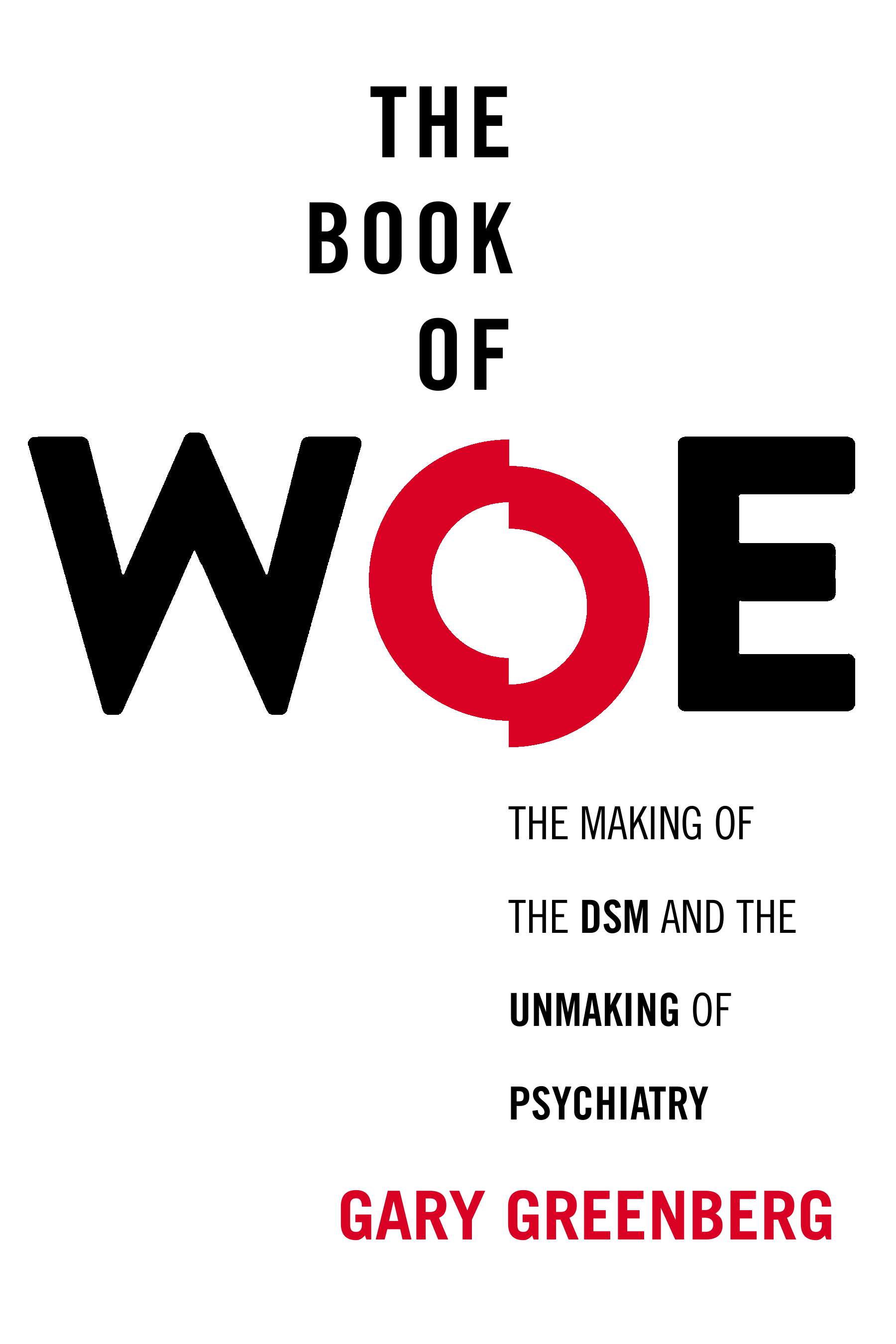

Sneak Peek

February 22nd, 2013

This is the cover for my new book. I think it’s self-explanatory.

If I were really savvy, I’d have posted this and the alternatives a long time ago and submitted to the wisdom of the crowd. But I’m not.

No Comments »

From the Mailbag

February 22nd, 2013

In response to my comment that maybe the DSM-5 doesn’t matter, Rebecca writes

Having a bipolar diagnosis will get you rejected from underwritten health insurance for the self-employed – even if you apply for a policy that specifically excludes mental health coverage (as I did). And you can’t get the faux bipolar diagnosis removed from your medical record because even if it’s a fad diagnosis there is no way to prove that you don’t have it once you’ve been labelled.

This is a great example of why the DSM does matter, even if the particulars of DSM-5 don’t (at least not so much). It’s also a totally underappreciated aspect of using medical insurance to pay for mental health treatment. The diagnosis your therapist puts on your bill, those innocuous-seeming 4 or 5 digits that he or she may or may not even mention to you or may assure you are merely a formality, will become part of your permanent medical dossier. And as electronic medical records become the law of the land, the diagnosis will not be something that someone has to dig around in the paperwork to find.

Rebecca writes of one of the implications: you might be denied health insurance in the future. In the Obamacare era, you won’t be denied, but you may well be put into the assigned risk pool, or whatever it is eventually called, and your premiums increased accordingly. But you may be denied life insurance and, who knows, as all our datalives converge in the Mother Computer, your credit rating, your car insurance premiums, your employment prospects, and so on may also be affected.

And that’s not all. I have a patient who has chronic illnesses that sometimes become acute and life threatening. Her array of symptoms and syndromes is so vast and complicated and confusing, and so confounded by the interactions among her treatments, that she stumps every doctor that comes into contact with her. Once, when hospitalized at a leading university medical center, a psychiatric evaluation was ordered, and she was diagnosed with Somatoform Disorder, largely on the basis of a Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory, an old-line personality test that has among its features a hypochondriasis scale. Conventional wisdom holds that the Hs scale is not valid for people who are actually sick (duh!), but that didn’t stop the clinician, a psychiatrist who spent 45 minutes with the patient and then read the test results, from rendering the diagnosis. Since that time, when she has been hospitalized, and especially when she has been hospitalized in a new (to her) hospital, doctors confronted with her bewildering array of symptoms have seized this one diagnosis to decide that she is a mental patient. She, naturally, objects, and I have often had to enter the fray to try to straighten out the situation–a job at which I am only partly successful.

Moral of the story (and of Rebecca’s comment): Be careful about getting yourself diagnosed. It can haunt you all your life. It might be worth shelling out your own hard-earned cash for therapy to keep yourself safe.

No Comments »

|

|

|