|

I smoked pot with David Brooks

January 3rd, 2014

Please note: What follows here is satire of the Juvenalian variety. I thought I embedded enough tipoffs, but then again I forgot how much stranger than fiction truth can be. So to those who thought it was real and suffered pain as a result, I apologize.

Now that he’s gone and outed himself, I guess I’m free to tell the secret. I smoked pot with David Brooks. I was one of that “clique” with whom he had “those moments of uninhibited frolic.” There were seven of us. We all know what happened to Dave. The rest: a surgeon (rich), a dentist (gay), two lawyers (one dead already), one teacher and one househusband/artist (that’s me). I never spoke up before because I figured if I threw mud at someone whose whole career rests on being squeaky clean, well, that’s just mean. And it’s mostly irrelevant now. I mean, like he said, we’ve “aged out” and “left marijuana behind.”

Well, all except me. I still get high from time to time. It helps me deal with the kids, makes me more playful and my knees ache less when I get on the floor with them. Dave would probably say I delayed having them until so late because I was too busy getting stoned, and maybe he’s right, although I like to think I was waiting for the right woman and the right time. Anyway, I gather he doesn’t have any problem with my once a week toking, even if it’s “not a particularly uplifting form of pleasure and should be discouraged more than encouraged.” So even if social scientists have proved smoking doesn’t really make me more creative (although I could swear it does, and I’ve heard others say the same, but what do we know?), and even if it makes it impossible for me to “graduate to more satisfying pleasures”–although marriage, kids, reading, music, conversations with friends, I used to think those were pretty satisfying– I guess I’m okay in his book.

Funny thing. I didn’t know before this morning that I was the “full-on stoner” who was one of the four reasons Dave gave up weed. Sorry as I am to hear that our frolics are now his shameful 4 a.m. memories, after all these years of silence, it’s nice to know I mattered to him, that I was a significant part of the moral life of someone so important and with such a strong “sense of satisfaction and accomplishment”—an achievement I guess I made possible by teaching him that “one sort of life you might choose is better than another sort of life.”

And here all along I thought he quit because of that time we got pulled over by the Radnor cops in senior year right after we’d clambaked his Mom’s Vista Cruiser, and first thing the cop does after the smoke clears is look him right in his red, red eyes, and said, “I don’t suppose it would go over so good if I went over to 632 Haverford Road and told Mr and Mrs Brooks their boy was out here with his clique smoking pot.” I was so impressed with the way Dave pulled himself together then. He didn’t beg for mercy or fight with the cop. Somehow he knew exactly how to go all bar mitzvah boy, how to talk to authority, how to flatter and impress and toady, even stoned to the gills, like his inner Eddie Haskell was deeper down than the pot could get. And it worked. The cop let us go, told us we were lucky he knew Dave and that we were white kids from Radnor, and later on, at the pizza house taking care of our munchies, chattering and cackling over our good luck and trying to figure out how Dave and the cop knew each other, busting on him for being a narc, Dave was quiet and pale and barely touched his hoagie, and I think that was the last time he smoked pot, at least with us.

But before that, did we have some uninhibited frolic! He wrote in his column about the time he got high during lunch and then “stumbled through” a presentation in English class. Too bad he didn’t go into the details. But I remember it pretty well. It was senior year. We all had to give a 10-minute talk about one of the leitmotifs in Lord Jim. We’d both chosen “one of us,” an idea that was totally DAve’s. He’d gotten after we smoked some insane Thai stick and went into Philly to see “Freaks” at the TLA. We’d figured out our talks on the train back home. Mine was going to be about how Conrad was being ironic, and the “us” weren’t exactly people you wanted to be one of. His was going to be about the way Jim’s “selfishness of a higher order” was a model for Hamiltonian government. Mine went off without a hitch, even though I was as stoned as he was. (But I was probably already the full-on stoner, so maybe I had a tolerance.)

But when Dave got up there, I think he was trying to be literary or casual or something, and he started in by saying that the idea had come to him watching Freaks, and he got totally sidetracked, the way you do when you’re good and high. “Oh, man, you shoulda seen it,” he said. “These, like, total freakazoids. This one? Prince something or other? No arms or legs, but he could roll a cigarette and then light it—with his mouth, man! He’d fit right in here at Radnor Get High…” and here he started giggling uncontrollably, and all he could say was “One of us, one of us, gobble gobble gobble” until Mr. Sedgwick had to tell him to sit down. (Later Dave told us he told Sedge he’d never done it before and he was really sorry and Sedge said he wouldn’t call his parents, but he (Dave) was such a good boy he knew he wouldn’t do that again.)

The other part he didn’t tell was about how we got high at lunch. This was back when you could smoke at school. Cigarettes, I mean, but naturally that wasn’t all we smoked. Smokers had to go to an area set up outside the cafeteria, hemmed in by the other wings of the building, sort of like a cell block. Architects must have been stoned or something, or maybe that was back when we didn’t care so much about smoking, but anyway they put the air intake for the second floor in a corner of the cell block. So we were smoking this joint of Jamaican over in that corner and Dave got the bright idea to blow the smoke into the register. “That’ll make everyone up there one of us!” he said. And sure enough when we went up to class the whole floor stank and the vice-principal was hustling up and down the hallway, wrinkling his nose like a bloodhound trying to figure out where the smell was coming from, and then he went into the boys’ room and dragged out one of the only two black boys at Radnor High, yelling at him for smoking pot in school.

I remember the guilty look on Dave’s face when he saw Mr. Santangelo with the kid by the collar. Later on, he told me that he was tempted to confess, but he also happened to know that that boy did smoke pot, that he was a full-on stoner, so if he got in a little trouble, it might be good for him. When I read today that Dave thinks that “not smoking, or only smoking sporadically gave you a better shot at becoming a little more integrated and interesting,” while “smoking all the time seemed likely to cumulatively fragment a person’s deep center,” I thought about that boy and wondered if getting kicked out of school had helped him hold together his deep center, and if his going to juvy was the kind of subtle discouragement that Dave thinks governments should engage in when it comes to the “lesser pleasures.” I suppose he thought he was doing the kid a favor by letting him take the rap.

There were other frolics, of course. Not with girls—Dave wasn’t much for the girls, all fumbly and mumbly and the pot just supersized his nerdiness. But culture and politics, those great interminable debates. Beatles or Stones, pipes or papers, negotiate over the hostages or send in the troops. Dave had a way of starting off all reasonable, usually talking about how both sides were equally bad. But the stoneder he got, the more opinionated he became, and his opinions—well, let’s just say that when Dave wrote this morning that in a healthy society “government subtly encourages the highest pleasures” I remembered a time we were parked out at French Creek and he stood up on top of the Vista Cruiser and gave a speech to us about what Jefferson really meant by the “pursuit of happiness,” and how a government should uphold our right to get as high as possible, and how George Washington grew pot and old Edmund Burke must have smoked it, and I wondered if Dave was sending his old posse a secret message. I wondered if, especially now that he’s past fifty and divorced and all that, he’s getting a little tired of maturity, of being harnessed to “the powers of reason, temperance, and self-control,” not to mention to the New York Times, he wanted us to come take him out and apply some subtle peer group pressure to his “moral ecology.”

Which we’d be glad to do. I just found the other guys on facebook. Flights to Denver are cheap. Pot tourism is already happening, we can buy a cheap package, maybe even find a Vista Cruiser to rent or an air register to blow our smoke into, bake a whole floor of the hotel. If you’re reading this, Dave, consider it an invitation. Let’s go encourage our lesser pleasures, relive those days before we aged out and got all inhibited and gray, give ourselves some new embarrassing memories to wake up to at 4 a.m. Because there’s only one thing worse than waking up in the wee hours reminded of what an idiot you can be, and that’s having nothing at all to trouble you, just the smooth satisfaction of success.

106 Comments »

Mistakes were made, Part 2

December 30th, 2013

So that was a textbook case of how to handle a mistake. And here’s the textbook case on how not to.

Richard Noll is a professor of psychology at DeSales University. He’s that rare thing–a mental health worker who understands history. His most recent book, American Madness: The Rise and Fall of Dementia Praecox, is terrific. When psychiatrists finally discover, as I am sure they will eventually, that schizophrenia is not a single disease or anything like a single disease, they will have to acknowledge Noll as one of the first people to say so.

Noll is no stranger to controversy. He wrote a book in 1994 called The Jung Cult: Origins of a Charismatic Movement. The book was published by Princeton University Press, which was pleased enough with it to submit it for a Pulitzer. It didn’t win, but the Association of American Publishers gave it its Best Book in Psychology award for that year. Princeton is also the publisher of Jung’s collected works, which is a beautiful and expensive multivolume set, one that most likely yields substantial financial rewards for both the press and the Jung family. So it’s no surprise that when the Jung family objected to Noll’s book, which made a splash in popular media, Princeton U Press decided to dump Noll, and pulled the plug on another Jung project he was editing for them, which was already in page proofs. I guess they decided it had been a mistake to let Noll bite the hand that was feeding them.

Full disclosure here: my wife wrote her dissertation on people who claimed to have been abducted by extraterrestrials, and back in the late 80s-early 90s, had some contact with Noll, who was also interested in that topic. She recently confessed that she liked him–although, she reassures me, not THAT way–and that makes me like him, because I like her. Noll’s interest in ET abduction was part of his larger interest in dissociation, the phenomenon whereby consciousness is split such that two separate selves can exist in the same body. It’s a weird occurrence, and an unusual one, thought mostly to be caused by extreme trauma, but I have no doubt it happens.

You may remember that at the end of the 1980s, about the time that my wife was crushing on him, the country was riveted by accounts of Satanic Ritual Abuse. In a word, there was a sudden outbreak of people, mostly children, claiming to have been forced by Satanic cults to witness and/or participate in heinous acts, like cutting out babies’ hearts and eating them, often in day care centers. The stories were disturbing and implausible, but they could not be refuted, because it is impossible to prove a negative. They were perfect fodder for a moral panic, and that is indeed what happened. The results included the jailing of over 100 day care providers (some of whom remain imprisoned), the sundering of some communities, and children unalterably confused about what had happened (or not happened) to them.

That’s a pretty lame summary, and I apologize, but I don’t want to get sidetracked by this fascinating example of the witch hunts Americans seem so good at. If you want more, there are plenty of good books on the topic, including this one and this one. What you can’t do, however, is to read the excellent article that Noll wrote on the subject very recently for Psychiatric Times–an article, as he explained, that he wrote because he felt that psychiatry’s role in the epidemic was in danger of being forgotten.

Despite the discomfort it brings, we owe it to the current generation of clinicians to remember that

an elite minority within the American psychiatric profession played a small but ultimately decisive

role in the cultural validation, and then reduction, of the Satanism moral panic between 1988 and

1994. Indeed, what can we all learn from American psychiatry’s involvement in the moral panic?

The article was short but comprehensive, well documented and informed by personal experience. He singles out two psychiatrists–Bennett Braun, and RIchard Kluft– who were instrumental in giving legitimacy to the SRA accounts. They helped change the DSM to make Multiple Personality Disorder (thought to be caused by the abuse) seem more common, they started the International Society for the Study of Multiple Personality and Dissociation, and they founded a journal called Dissociation.

Noll was one of the earliest mental health professionals to try to cast doubt on these outlandish tales. In the article, he reocounted his appearance at the 1990 ISSMP&D annual meeting, a conference attended by, among others, Gloria Steinem.

The 4 members of the plenary session panel were [psychiatrist Frank] Putnam, [psychiatrist] George Ganaway, anthropologist Sherrill Mulhern, and me. Putnam had read my Dissociation critique and wanted me to present my argument in person. Putnam and Ganaway presented carefully balanced arguments that did not directly reject the reality of SRA. Instead they expressed concerns about the linkage of MPD to such controversial claims, noting it would hurt future research on child abuse and trauma.

Mulhern and I were strident in our outright rejection of the veracity of SRA claims. She cited

anthropological and sociological research while I hammered home the view of historians that ancient

accounts of bizarre cult practices had to be read in context. Along with my fellow panelists, I too

mentioned the October 1989 preliminary report of an investigation by Supervisory Special Agent Ken

Lanning from the FBI Behavioral Science Unit at Quantico which found no corroborating evidence of

the existence of Satanic cults engaged in any criminal activity, let alone kidnapping and ritually

sacrificing thousands of American babies. Lanning’s findings had emboldened Putnam to organize

the special plenary session and go public with his private skepticism. The full FBI report appeared 3

years later.

Gloria Steinem approached me after my talk and suggested materials to read which she felt would

help me change my opinion of SRA accounts. During the conference I attended one of [psychiatrist] Bennett Braun’s legendary SRA workshops (“See the Satanism!” he screamed as he pointed to a patient’s red crayon scratching on a sketch pad. “There it is!”). Several persons—all licensed mental health professionals—approached me and let me know I wasn’t fooling them. They knew I was a witch or a member of a Satanic cult who was there to spread disinformation. But apparently the panel

presentations had a different effect on others. As one conference attendee, an SRA believer, later

wrote, “Mulhern and Noll cut a line through the therapeutic community. A minority joined them in

refusing to believe sacrificial murder was going on; the majority still believed their patients’

accounts.”

Noll sent the article to Psychiatric Times, an independent online and print journal that provides comprehensive coverage of the profession. The editor’s response was enthusiastic. “We all think your essay is terrific,” she wrote. Not only would they love to publish it on the web, she added, but “I thought right away that it would work in print.” Indeed, she wrote, “We all love the article and are thinking of using it as one of the cover stories for our January issue.”

On Dec. 6, the article was posted on the PT website. It almost immediately earned a complimentary tweet from Allen Frances and a mention on h-madness, a website for psychiatric history buffs. The editor made some suggestions for the print version and asked for Noll to finish them by Dec. 16. But then on Dec. 14, Noll discovered that his article had vanished from the website. He made gentle inquiries and determined that it wasn’t a glitch, but that PT had intentionally taken down the article. The reasons were vague–something about how they didn’t like the title (which they had chosen), and how they didn’t like the fact that he had named names. But whatever the reason, the article was gone.

Earlier this week, Noll finally demanded a full explanation. And he got one.

Dear Dr. Noll,

I don’t blame you for being miffed at the inexplicable disappearance of your article, and the long delay in getting back to you with an explanation. I’d like to offer a sincere apology for the delay, and to explain what happened. It hasn’t helped that our offices were closed most of last week and that communications between editorial board members and staff have been generally slow because of vacations.

As you know, Professor [redacted] is the final arbiter of History of Psychiatry columns, so our staff enthusiastically went ahead and posted your article. I read it the weekend it was posted, however, and grew immediately concerned that it raised potential liability issues—possibly for you and, by extension, for Psychiatric Times. I therefore thought it prudent to hide the piece from public view until I could get some guidance from our editorial board. The board did support these concerns, and it was suggested that I consider obtaining corporate legal advice. There was also the suggestion that Drs. Kluft and Braun and some others discussed in your essay needed to be given the opportunity to respond to claims made in the piece. However, there was also general consensus that the piece “may be of some historical interest, but not particularly relevant to the problems facing psychiatry today.” Ultimately, it was the board’s recommendation that we not publish the piece.

We respect your expertise and previous contributions to Psychiatric Times. The scenario is a first for us. I’m so sorry it happened this way. We will return your copyright form and hope that you find another venue for the piece.

This explanation is so far to the stoat end of the weasel scale that it’s hard to know where to begin–particularly given PT’s reputation (deserved, as near as I can make out) for not flinching from controversy. (After all, they gave Al Frances the launching pad for his jihad against DSM-5.) Blaming the enthusiasm on Professor [redacted]? Claiming to have been unaware of the article until after it was posted, and then immediately smelling a rat? Mentioning lawyers without mentioning whether or not they were actually consulted? Suggesting that it was somehow too late to get rebuttals? A board recommendation to not publish an article that had already been published? Sorry that it happened this way, as if it would have been okay to do this if they’d been nicer about it? I mean, my God, as if the removal of the article wasn’t contemptuous enough, the least they could have done was to come up with a story that showed some respect for Noll, and for readers, and for history, and for all those poor schmucks still in jail for feeding baby hearts to children.

Whatever, the point is that suddenly the essay wasn’t so terrific. It wasn’t cover story material. It wasn’t even worthy of being left on the website. It needed to be removed, forgotten, repressed.

You can read the article here. It’s definitely worth your time. But you can trust me on this. I’ve gone through some really grueling legal reviews conducted by expensive New York lawyers who smell lawsuits the way blue tick hounds smell raccoons. And I’ve taken on, in pretty abrasive terms, some very deep-pocketed people. So I have some sense of what is actionable and what is not. And I just don’t see the “potential liability issues.” It’s a nice, concise, simple history of a less than stellar moment in the history of psychiatry. Every statement is documented; most are taken from public records, and the rest are from Noll’s direct experience. All he is saying is that psychiatry made a mistake and needs to learn from it, and he’s pretty darned gentlemanly about it, especially for someone who blew the whistle early on. This is about as strong as it gets:

The resounding silence of the elite psychiatrists could only be interpreted in three ways by those of us “in the trenches” who looked up to them for guidance: these Satanic cults were real (despite the lack of corroborating physical or forensic evidence); the experts did not know if they were real and were afraid of insulting the patients; or there was an abject failure of ethical leadership.

Of course, I’m not a lawyer and I don’t play one on tv. So I could be wrong. Maybe some lawyer somewhere could find a way to sue him for libel or defamation. But, especially given that the journal loved the article enough to publish it, isn’t it at least the sporting thing to tell Noll what the liability worries are and allow him to address them? And as for the “not particularly relevant” excuse, well, that’s just laughable, given how enthused they were with the article. So what’s the real story?

Noll is way too much of a mensch, and of a careful scholar, to speculate out loud. But no one wants to be reminded of an abject failure, least of all a profession that sometimes seems to specialize in them (did you see the reports this week that the studies proving that stimulants were the best treatment for ADHD were flawed?), and even less the individuals who made the mistakes and who, after the edifice collapsed, brushed off the dust and got on with their professional lives. I’m figuring that Noll embarrassed some influential people, and they had more pull than he did with Psychiatric Times, which reacted by expunging him, in exactly the same way that the mind, confronted with something it can’t tolerate, pushes it into the unconscious.

So mistakes were made, all right. And unlike PsycCritiques, Psychiatric Times has done everything in its power to deny responsibility for it. LIke I said, a textbook case.

One of the reasons Al Frances is a hero in so many people’s books (including, at least in some ways, mine), is that he has tried to take responsibility for abject failures of ethical leadership, or at least has been honest enough to admit they have occurred. That this kind of candor is so rare within psychiatry is a signal that there is something rotten deep within its professional culture.

9 Comments »

Mistakes Were Made, Part 1

December 30th, 2013

We all make them. And, as the other cliche goes, when we do we can learn from them. Not only that, but our response to them reveals who we are, or at least who we wish to be.

That’s why, when I insulted my ex-wife in a public forum and she objected, I apologized right away and without qualification. Not because I’m such a good guy. I’m not. But I asked myself who I wanted to be in that situation, and the answer was, the kind of person who apologizes right away and without qualification. So I did. It was painless, and she was gracious, and it was over.

Now not every situation is that straightforward. But in the last couple of months, I’ve seen a couple of mistakes get made, mistakes much more serious than my regrettable lapse, in both cases by professional journals, and the difference in response has been telling.

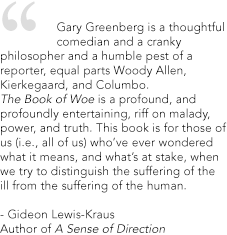

The first mistake was committed by an American Psychological Association journal called PsycCritiques. A couple weeks before Thanksgiving I got email informing me that the journal had just published a review of my book. I clicked the link. There I discovered a review written by Peter Nathan, professor emeritus of psychology and public health at University of Iowa. It was totally serviceable, save for a couple of details, which you will glean from the email below:

Dear [editor of journal]

Thanks for alerting me to this review. I generally do not respond to reviews, but I’m afraid I must bring a serious problem in this review to your attention.

In the review, Dr. Nathan writes,

“What you will learn is what Greenberg quotes his interviewees—many of them principal players in the conflict—as thinking and saying about others involved in the conflict. Much of this material is fascinating, although the credibility of some of Greenberg’s interview material is uncertain. I am inclined to take parts of it with a grain of salt and be entertained by all of it.”

I’m glad Dr Nathan was entertained, but if I am reading this correctly (and I am not sure I am; the passage is not entirely clear), he is suggesting that I have fabricated interview material. That is a very serious charge, and I am surprised that you allowed it to be published without offering me an opportunity to respond, especially in the absence of any evidence for it. (I am distinguishing here between an opinion about the merits of a book, which of course Dr Nathan is entitled to express without my input or knowledge, and an allegation about my integrity.) I am fully prepared to prove that every quote in The Book of Woe is accurate; every interview was transcribed and the voice file archived. I would also point out that although many of the people quoted are unhappy about the way they were depicted, not one of them has ever challenged the accuracy of the quotes.

I note that earlier in the essay, Dr Nathan cites a quotation from Darrel Regier regarding Allen Frances, and then goes on to quote further from my book in the extract that ends, “Blinded by pride…” Again, Dr Nathan’s prose is a little hard to parse, but from his subsequent comment, “These are surprisingly unrestrained comments by Regier,” it would appear that he thinks that the extracted material is a quote from REgier. It is not. It is my gloss on Regier’s comment, and there is nothing in the Book of Woe that would indicate otherwise.

I mention this in part because it is possible that Dr Nathan’s skepticism may be based in part on the unlikelihood of Regier ever saying anything like this. If that is the case, then the problem here is compounded: he is offering as evidence for his serious charge about my credibility a quotation that any reasonable person familiar with the DSM-5 (including me) would agree is indeed incredible–if its source is alleged to be Regier. That is Dr Nathan’s error, not mine.

Of course, it is entirely possible that I am misreading Dr Nathan, although it’s hard to find a meaning other than the one to which I am objecting–that he is alleging dishonesty on my part. But if that is somehow the case, then I would ask that you re-edit that sentence to convey the meaning that Dr. Nathan intends. I also think you should clarify that the extract that includes the comment about Frances’s being blinded by pride is not a quote from Regier. Finally, and most important, I must insist that you either get DR Nathan to cite his evidence for his charge and allow me an opportunity to respond, or remove it from the review.

I wish I could take this with a grain of salt, be entertained, and move on, but I make my living in part as a writer of nonfiction, and I cannot afford to have my honesty questioned in this fashion. I hope you can appreciate the seriousness of this matter, and its urgency for me. I fully intend to be collegial and cordial about working this out, and you will find me a very reasonable negotiator,m but rest assured I will not hesitate to take legal action against you and Dr Nathan if we cannot reach a satisfactory accommodation.

You may reach me by email or atxxx-xxx-xxxx

Regards,

Gary Greenberg, Ph.D.

Now, to their great credit, PsycCritiques responded immediately and worked with me over the next couple of weeks to solve this problem. They were a little slow to remove the review from the site while it was being revised, but otherwise they were cordial and collegial and ultimately changed the text and ran a correction, linked to the original article. The correction was unequivocal. See for yourself.

Correction to Nathan (2013)

http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0034634

This is a correction to a previously published article: DSM–5: The Perfect Storm

The review “DSM–5: The Perfect Storm” (PsycCRITIQUES, Vol. 58, No. 45, Article 3) contained three errors.

1. In the paragraph that begins “For example, Greenberg quotes Regier as remarking,” the full paragraph should read as follows:

For example, Greenberg quotes Regier as remarking, of Frances, as early as 2010, “His major critique [was that] nothing has changed in the scientific world since his revision and hence no substantive revision is possible” and “that his judgment on the pragmatic consequences of revisions should take precedence over any of the experts” (p. 138). In other words, according to Greenberg’s understanding of Regier’s comments, Frances was

trumping up his personal grievance into a broadside against the institution he once served and in the bargain calling into question the credibility of the APA. . . . Blinded by pride, he had become his own kind of antipsychiatrist and, even worse, a turncoat. (p. 138)

2. The sentence immediately following the quotation above should be deleted. That sentence read as follows: “These are surprisingly unrestrained comments by Regier, presumably speaking for both himself and Kupfer.”

3. In the paragraph titled Final Word (referring to The Book of Woe), phrases in the third to last and second to last sentences should be deleted, and the last three sentences of the paragraph should read as follows: “Much of this material is fascinating. I am entertained by all of it. Greenberg writes very well.” The deleted phrases are underlined in the following two sentences from the original review:

Much of this material is fascinating, although the credibility of some of Greenberg’s interview material is uncertain. I am inclined to take parts of it with a grain of salt and be entertained by all of it.

The deleted text conveys the impression that Greenberg had fabricated the quotations. There is no evidence for this assertion. It should not have been included in the original article, and PsycCRITIQUES regrets the error.

The review has been modified to reflect the above edits.

This is a totally menschy apology. It made me feel better, it righted a wrong, and it closed the book on this issue. In other words, it did exactly what an apology was supposed to do. And it would have receded into the backroads of my memory had it not been for an incident that occurred a couple of weeks later, which I will write about in my next post.

No Comments »

Where’s my DSM-5?

October 10th, 2013

Back in 2012, I participated in the field trials for the DSM-5. 5000 clinicians enrolled in the Routine Clinical Practice trial. It was a trial in a way that I don’t think the American Psychiatric Association intended, and only 700 of the enrolled persisted through the training, the paperwork, and the incredibly tedious interview process long enough to complete it. I am proud to say I was one of them. I wrote about this in The Book of Woe, so you can read about it there if you haven’t already.

The APA promised us collaborating investigators (a name whose VIchyesque overtones sort of creeped me out) a few goodies in return: Some continuing education credits, a frameable certificate, our names in the back of the book, and a free copy of the DSM-5. That’s a $200 value, which, after the eight hours of training and the six hours of running the trial, comes to about $15/hr., which is more than I would have made at McDonald’s.

I did get my certificate, which even came with a black mat. I got my CEUs. I got a nice letter thanking me for my service. And late in May, a week after the DSM-5 was released, I got this positively effusive email from Lisa Countis, the manager of field operations for the APA.

From: Lisa Countis <xxxxxxxx@psych.org>

To: ApaResearch <xxxxxx@psych.org>

Sent: Friday, May 24, 2013 5:18 PM

Subject: DSM-5 Field Trials Participants: Delivery of your DSM-5

Dear Collaborating Investigators,

The DSM-5 was released to the public on May 22nd. Your copy of the new DSM will ship from the publisher within the next few days and should arrive within 2-3 weeks. Thank you again for your support and participation in the Field Trials – your input played an important part in the refinement of the diagnostic criteria. Additionally, the input we received from you throughout the study recruitment, training, and implementation process has been invaluable in informing subsequent DSM-like studies. We have learned a lot from you!

Well, those 2 or 3 weeks have come and gone many times, and I still don’t have my DSM-5. It’s hard to imagine that, after all my support and participation and all the influence I have had on DSM-like studies and all they learned from me, they would stiff me. But I have emailed Lisa Countis a few times. I’ve been cordial and polite and she initially was cordial and polite back, promising to look into it that very day. But I never heard back. And now she’s not returning my emails.

I suppose it’s possible this is just an accident, but somehow I think this might reflect a certain, I don’t know, animosity on the APA’s part toward me. Now I can understand them being so sore with me that they wouldn’t want to send me a free copy of the DSM-5. But they should have thought of that before they promised me one, or, for that matter before they let me into their clinical trial. Not only that, but their book is #15 in the amazon rankings, better by an order of magnitude than mine, and the least they could do is be magnanimous in victory. Besides, a deal is a deal, right? And if they don’t make good on it, I’ll never know–unless I shell out the two hundred bucks (actually, it’s down to about a hundred on amazon, but that is still a hundred dollars more than it costs to download the ICD codes, which will suffice for my clinical purposes)–if my name is indeed in the back of the book.

So I’m asking for a little help here. I don’t want to flood Lisa Countis’s email box, but the APA’s research arm has a general mail box. It’s aparesearch@psych.org. Perhaps you could drop them a line urging them to make good on their promise and liberate my copy of the DSM-5. Maybe tell them that it doesn’t look good when an organization so crucial to the social and moral life of our society doesn’t honor its promises. Or that it looks really menschy when you play nice with your critics. Anyone who can prove they were instrumental in getting me a copy will get a nice signed hardcover version of Manufacturing Depression (while supplies last) and my everlasting thanks. I promise!

4 Comments »

Indolent Lesions

September 20th, 2013

This will be the name of my next band. It’s also the name that the National CAncer Institute has suggested for certain “non-malignant conditions” that are currently called cancer, like ductal carcinoma in situ, a lesion that often shows up on mammograms and scares the bejesus out of women, not to mention leads to all sorts of treatments. “The word ‘cancer’ often invokes the specter of an inexorably lethal process,” an NCI panel wrote in JAMA. “However, cancers are heterogeneous and can follow multiple paths, not all of which progress to metastases and death, and include indolent disease that causes no harm during the patient’s lifetime.” And detection of these indolent lesions, they continue, can be dangerous because it leads to unnecessary procedures.

I remember when my first wife got one of those phone calls about a funny mammogram, the kind that only come on a Thursday or Friday and leave you to worry all weekend. By the time we got to the follow-up visit early the next week, we were both nervous wrecks, she, understandably, more than I. As we were crossing the street to the hospital, she realized she had forgotten something in the car, which upset her even more. She spun around to return to the car. The pavement was a little wet from an earlier rain, and she slipped and fell. She was not injured, but it was the kind of accident that happens when you feel like your life is out of control, and seems to embody your situation. For a moment it seemed like misfortune would just cascade forever.

She turned out to be fine. Even better, the tests didn’t require all that much of her (aside from the time and worry)–no needle biopsies, no radiation-assisted scans, no knives. But that;s not always the case. Many of these screening tests–mammograms, pap tests, PSA assays–turn up “precancerous” or nonmalignant conditions on a frequent basis and lead to what the NCI panel calls overdiagnosis, which in turn leads to overtreatment. Between the stress of the diagnosis and the dangers of the follow-up tests and treatment the problem is a serious one. And much of it can be attributed to the effect on both doctor and patient of the word “cancer.” So, the panel reasonably concludes, the “the term “cancer” should be “reserved for describing lesions with a reasonable likelihood of lethal progression.” If it probably won’t kill you, in other words, it doesn’t deserve to be called cancer.

By recognizing the effect of nomenclature on people and on the society that pays for these treatments, these doctors are taking responsibility for unintended consequences of their profession’s actions. They’re implicitly acknowledging that some of those lopped off breasts and excised prostates have been sacrificed without cause, and that the harms suffered–pain, disfigurement, impotence, incontinence, surgical complications–have been unnecessary. They’re not hiding their proposal in a murky claim about the science demanding these changes, as if some new instrument had allowed them finally to map the boundaries of cancer, but rather acknowledging the contingency of those boundaries and suggesting that they be renegotiated for what amount to pragmatic and social reasons, not scientific ones.

Contrast this with the American Psychiatric Association’s studied avoidance of acknowledging the pragmatic and political motivations behind some of the changes they made in the DSM-5, especially the change in the ASperger’s diagnosis. The APA was surprised to hear that the diagnosis had bestowed an identity on people with Asperger’s–a naivete that seems nearly willful, given the high profile of the disorder and the idea of “neurotypicality” that is spawned. And they were adamant in denying that they were trying to rein in the diagnosis or do anything of the sort, resorting instead to scientific mumbo-jumbo that was embarrassingly ineffective and only highlighted even further the contingent nature of the category. Of course, they can’t exactly do that, because unlike oncology, psychiatry can never touch bottom; there is no end to the contingency and uncertainties of psychiatric diagnosis, whereas an oncologist can at least see a neoplasm, even if they have to struggle over what to name it. So psychiatrists have to avoid what the cancer docs can face head on. What is straightforward, even common sense, for cancer doctors is taboo for psychiatrists. This is probably why the APA hasn’t seized on the very public NCI statement and used it as an illustration of its claim that psychiatry just isn’t that much different from the rest of medicine.

But there’s something else about the NCI paper that should really grab attention. It;s right in the opening paragraph.

Over the past 30 years, awareness and screening have led to an emphasis on early diagnosis of cancer. Although the goals of these efforts were to reduce the rate of late-stage disease and decrease cancer mortality, secular trends and clinical trials suggest that these goals have not been met; national data demonstrate significant increases in early-stage disease, without a proportional decline in later-stage disease.

I think what they’re saying here is that they’ve managed to identify (and presumably treat) a lot more early-stage disease, but not to prevent late-stage disease, i.e., death from cancer. Early detection, in other words, doesn’t necessarily improve the picture for many cancers. What it does do is to identify and treat succesfully a lot of cancers that might not have gone on to kill people, or even harm them for that matter. So the claim that medicine has gotten better at treating cancer, the one you see in ads for cancer centers or hear about from proud oncologists, is not as true as we might like. The number of successfully treated cancers has certainly gone up, but so has the overall number of cancers, and many of those “successful” treatments were also unnecessary. I don’t think anyone has done this on purpose, but the overall effect here is disconcerting.

2 Comments »

|

|

|